Magnetism and the Western Esoteric Tradition

This presentation explores the relationship between hypnosis and the Western esoteric tradition. From ancient times to the modern era, religious and philosophical societies in the West have fostered the concepts of a universal fluid and astral body. We will consider how these ideas gave rise to the healing practices of magnetism, mesmerism, and hypnotism. Along the way we discover some of the most intriguing phenomena and applications of these practices, such as energy healing, medical intuition, medicine at a distance, aura reading, and even spirit communication.

Understanding the history of magnetism and its relationship to the Western esoteric tradition helps us recognize that hypnosis has always been more than a technique of verbal suggestion. Many of the phenomena explored by early magnetizers—altered states of consciousness, intuitive insight, emotional transformation, and non-ordinary perception—lie at the foundation of modern hypnotherapy, even if they are no longer described in the language of fluids or subtle forces. By tracing how these ideas developed, we gain a clearer sense of the deeper capacities of the unconscious mind and the broader range of hypnotic experience available beyond suggestion alone.

This account explores three phases: first, the development of Mesmer’s animal magnetism; second, the integration of magnetism into the esoteric currents of the eighteenth century; and third, the continuation of esoteric and magnetic practices after the French Revolution, in the nineteenth century.

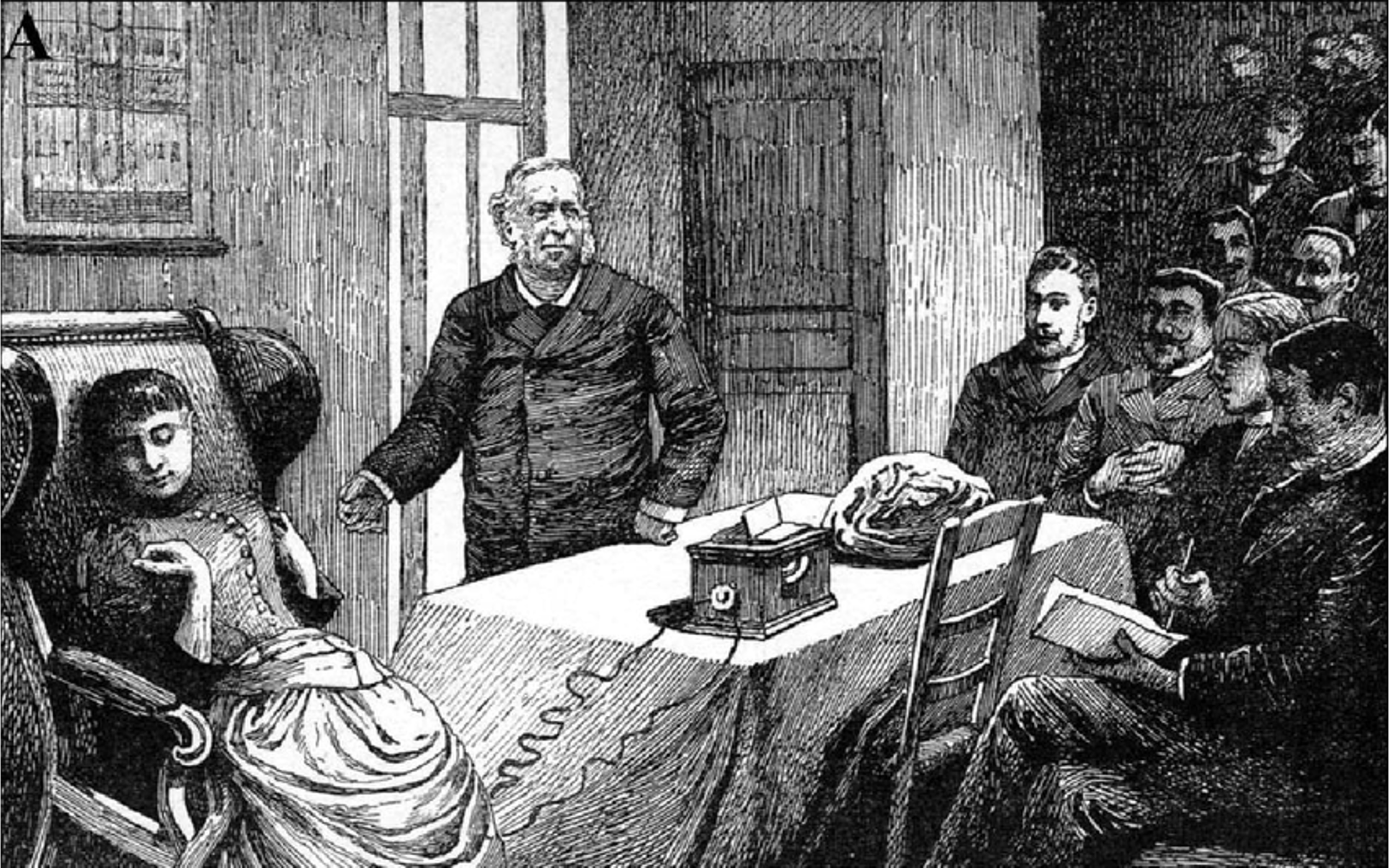

“Application of magic to a hypnotized subject. Influence of numbers.” From La magie et l'hypnose by Papus.

Audio version here. Text below.

Emphasis on Suggestion

The practice of hypnotism today emphasizes the hypnotic phenomenon of hypersuggestibility. That means when you are in hypnosis the unconscious mind is readily influenced by the ideas that are communicated by the hypnotist. In the typical experience of hypnotherapy, the hypnotist induces and deepens trance, then delivers verbal suggestions and guides the subject through imagery in order to influence the unconscious. This can be highly effective, but suggestion is only one aspect of hypnosis.

Before we go beyond suggestion, let's consider how it came to dominate the practice of hypnotism. The study of suggestion and suggestibility became prominent in the late 1800s with the work of two French physicians. First there was Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault, who can be considered the father of modern hypnotherapy. Liébeault was the co-founder of the Nancy School, also known as the Suggestion School, along with another prominent French physician, Hippolyte Bernheim. They showed that people can enter hypnotic states simply by verbal suggestion, without magnetism. In their view hypnosis was not produced by a magnetic or physical force, but instead was a psychological phenomenon resulting from the power of suggestion, like a placebo effect. This view was part of a shift in late 19th-century medicine toward recognizing that mental states influence physical health, and that not all illness had purely organic causes. Since that time, most people think about suggestibility and verbal suggestions when they think of hypnosis and hypnotherapy.

Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault

Hippolyte Bernheim

But just because hypnosis can be induced by suggestion does not mean that suggestion is the only way to induce hypnosis. In reality there are other factors involved in the hypnotic experience - ideas that were once the very foundation of hypnotism, but are now unfairly dismissed. We will explore these ideas by looking at their most famous proponent, Dr. Mesmer.

Mesmer

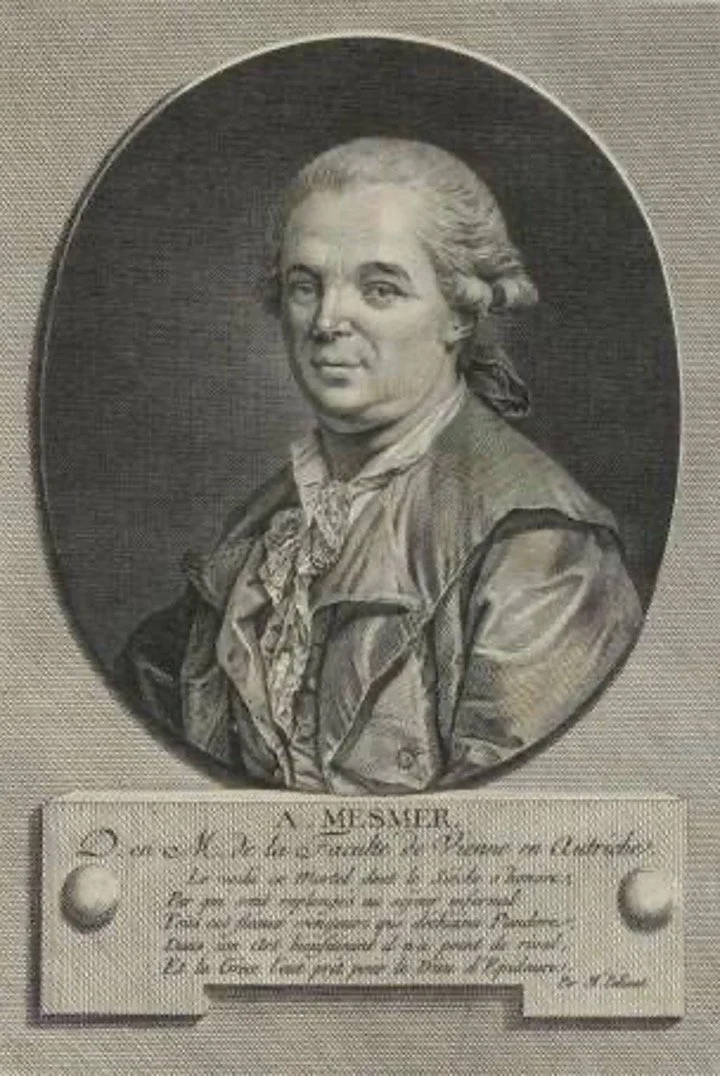

Franz Friedrich Anton Mesmer (1734-1815) was a German physician born in 1734, who formulated his theory of "animal magnetism" in the 1770s, while practicing medicine in Vienna.

Mesmer graduated from the University of Vienna if 1766. In his doctoral dissertation De planetarum influxu in corpus humanum (On the Influence of the Planets on the Human Body) he argued that the planets, especially the moon, have an effect on human health through their gravitational pull, which he believed influence the body’s internal fluids.

Franz Friedrich Anton Mesmer

Mesmer started his medical career with a focus on bloodletting and other traditional treatments of the time, which were based on the theory of bodily humors. He was also influenced by the ideas of Paracelsus, a Swiss physician and alchemist who was influential over 200 years earlier, during the 1500s. Paracelsus rejected the idea of bodily humors. He was one of the first to emphasize the existence of a vital force (or life force) and its role in health. He believed in the existence of invisible forces - spiritual fluids or subtle energies that influence vitality, health, and disease. For Paracelsus, health depended on maintaining the proper balance and flow of these forces, and disease was the result of blockages or disruptions. Here we already see the beginnings of the idea of an invisible magnetic fluid.

Another influence on Mesmer was that magnetic healing was becoming a popular trend in Europe. The Royal Astronomer in Vienna, a Jesuit priest named Maximilian Hell, had become famous for healing with steel magnets. In the early 1770s, Mesmer became acquainted with Hell and began experimenting with magnets in his own medical practice. He even borrowed Hell’s magnets.

Paracelsus

Maximilian Hell

Mesmer was also inspired by Johann Joseph Gassner. Like Maximilian Hell, Gassner was a Catholic priest. Gassner believed illnesses were caused by demons or invisible forces and could be cured by commanding those forces to leave. His dramatic healing sessions drew huge crowds across Europe. Mesmer observed Gassner’s work and concluded that it wasn't demonic exorcism that was responsible for the cures, but rather a natural magnetic force acting between bodies.

Finally, in addition to the popular healers of the time, Mesmer was influenced by the scientific climate of his time, particularly the work of Isaac Newton and the emerging ideas about physical forces. Giovanni Battista Beccaria inspired Mesmer with his work on magnetism and electricity. The bioelectricity experiments of Luigi Galvani also may have reinforced Mesmer's ideas about invisible forces.

In this environment of bodily humors, magnetic healing, and the scientific discovery of invisible forces like electricity and magnetism, Mesmer developed the idea that the human body was surrounded by an invisible fluid, which he termed the “magnetic fluid”. He wrote in his memoirs, “Animal magnetism is that universal force which is found in all living beings, and which is capable of acting on them.”[1] In 1776 Mesmer gave his first public demonstration of his methods in Vienna. In 1778 he published his first formal writings on animal magnetism, further elaborating on the magnetic fluid theory and explaining his methods.

At first, Mesmer’s method involved placing magnets on or near a patient’s body to direct the flow of the magnetic fluid. However, he soon found that he could achieve similar effects by using his hands alone, manipulating the fluid with direct contact or even by gesturing at a distance. As he explained in his writings, “The use of magnets can serve only to stimulate the patient’s magnetic fluid, but it is not necessary for the cure.”[2] Mesmer believed that certain individuals, like himself, had an innate strength in this magnetic force, which enabled them to heal others. He wrote, “There are some men in whom the fluid is more abundant, more concentrated, and better distributed than in others.”[3]

The patients frequently experienced intense reactions, including convulsions and trances, which Mesmer saw as "crises" essential for healing. These dramatic episodes contributed to the growing reputation of his practice. By 1780, Dr. Mesmer was treating at least 200 patients daily. His popularity led to widespread public interest, sometimes referred to as “Mesmeromania.”

Of course, this attracted attention. In 1784 Mesmerism was investigated by two Royal Commissions, which conducted a double-blind trial of patients and determined Mesmer's cures to be the effect of imagination, imitation, and touch, rather than the invisible fluid that Mesmer asserted.

This is where most histories of hypnotism cast Mesmer aside and repeat the opinion of the commission that the healing effects of mesmerism, or these days of hypnosis, are the result of belief and suggestibility alone, like a placebo effect. Since then Mesmer has been regarded as a key figure, but a misguided one at best, and at worst a charlatan.

But… there was a minority opinion on the commission, which pointed out several important facts:

First, Mesmer’s techniques often seemed to interact with the physical body in a way that was difficult to explain through psychology alone.

Second, the trances, convulsions, and physical improvements were too consistent and too powerful to be explained purely by suggestion or placebo effects.

Finally, and most significantly, Mesmer himself was never actually investigated! He was not even present at the investigations. Instead, the commission investigated Mesmer's student, Dr. Charles d’Eslon, who already had publicly separated from Mesmer.

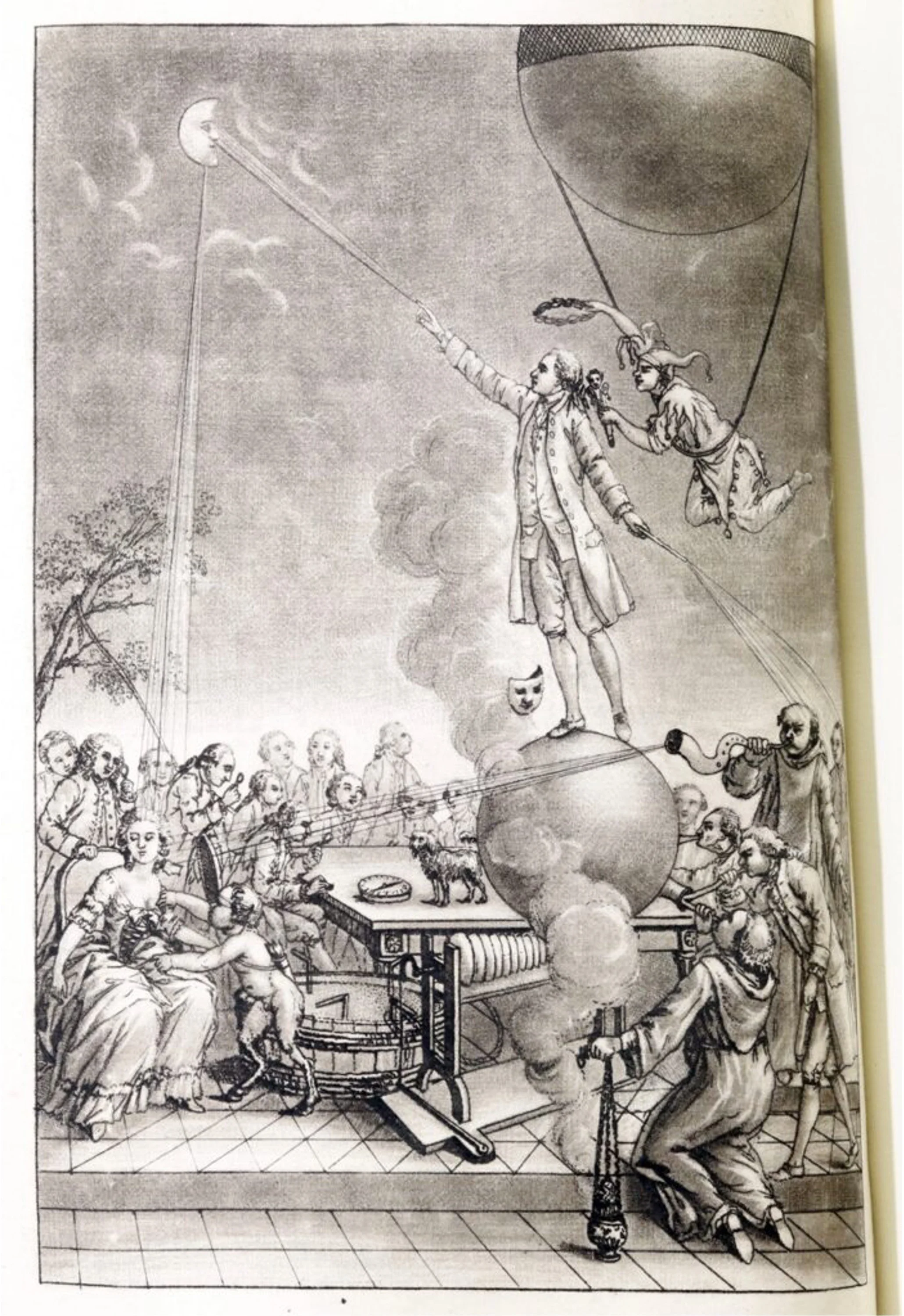

Anti-Mesmer propaganda: Mesmer is crowned by a jester as he stands on a balloon inflated by his followers, including a cleric, calling down the power of the sun to cure his patients.

Mesmeric Masonry and Spiritist Practices in Lyon

The continued development of magnetism and the fluidist theory is fascinating.

Mesmer's practice was meant to be therapeutic. However, many of his patients exhibited a range of extraordinary effects, including clairvoyance, telepathy, and somnambulism. These phenomena continued to be investigated, especially in the context of a new movement known as “Mesmeric Masonry”.

In Mesmer's time, the Age of Enlightenment, there was a great proliferation of esoteric masonic and chivalric orders descending from the Rosicrucian, Templar, and Kabbalistic traditions. Within these societies magnetism was actively explored.

In 1782, in Paris, Mesmer established his own society, called “The Order of Universal Harmony.” It was based on the principles of animal magnetism, and had a form of initiation by which Mesmer claimed that initiates were purified and made more fit to practice magnetism. In both 1782 and 1785 Mesmer attended important masonic conventions and met with important figures, such as Saint-Martin, St. Germain, and Cagliostro.[4]

Mesmerism and Mesmeric Masonry flourished in Lyon, France, which for centuries had been a stronghold for mystics and esotericists. Earlier, Martines de Pasqually, a kabbalist, Freemason and magician, had formed his Rite des Élus Cohens, or Elect Priests. His two main students, Louis Claude de Saint-Martin and Jean-Baptiste Willermoz, became central figures in the Western esoteric orders that persist to this day.

Martines de Pasqually

Martines de Pasqually

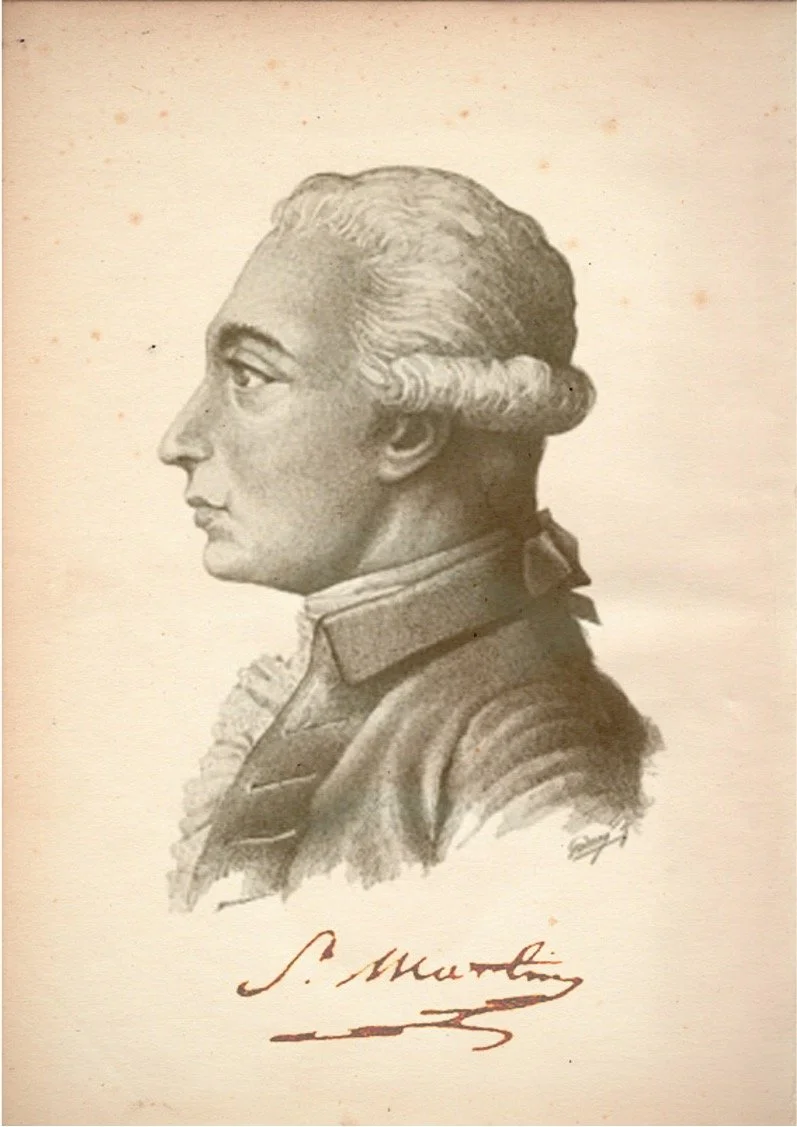

Louis Claude de Saint-Martin

Louis Claude de Saint-Martin (1743-1803), known as the Unknown Philosopher, was the most important mystic of his time. Saint-Martin settled in Versailles in 1778, the same year that Mesmer arrived in Paris; and in 1784 he joined Mesmer’s Order.

Having witnessed the operations of magnetism, Saint-Martin wrote (June 16, 1787): "In these magnetic experiments we see that men act upon one another in ways that do not belong to the senses... These operations show that there are forces in us which our philosophy does not explain.”

He also wrote regarding magnetism (March 2, 1785), “One cannot deny that these effects prove a commerce between souls that is not material.”

Louis Claude de Saint-Martin

Jean-Baptiste Willermoz and Chevalier de Barberin

Martines de Pasqually’s other well-known student, Jean-Baptiste Willermoz (1730-1824), was a prominent Mason in Lyon. He played a key role in transmitting the mystical teachings of Pasqually and guiding initiates within Martinist and Masonic circles, notably as the primary figure shaping the Rectified Scottish Rite. In 1773 Willermoz had become affiliated with the German Masonic Rite called the “Rite of Strict Templar Observance,” into which he integrated Pasqually’s Élus Cohen. He founded a Strict Observances Lodge in Lyon, La Bienfaisance, which in 1778 became known as the Knights Beneficent of the Holy City (Chevaliers Bienfaisants de la Cité Sainte, CBCS).

In 1784, the mesmerist society La Concorde was established in Lyon by Chevalier de Barberin, who was in the entourage of Willermoz. A contemporary statement on Barberin described him:

“Whilst the Marquis de Puysegur was making converts in every direction, by his wonderful somnambulists [i.e. highly hypnotizable subjects], a magnetizer of a still higher tone appeared on the scene in the person of the Chevalier de Barberini, a gentleman of Lyons, whose magnetic processes, associated with prayer, produced results even more extraordinary than the clairvoyants of Puységur.”[5]

Willermoz joined La Concorde soon after it was established. This mesmerist society recruited largely from Willermoz' Knights Beneficient, so Mesmerism was interpreted in light of their esoteric knowledge and practice.[6] Willermoz and the mystics of Lyon used magnetism, both therapeutically and to explore the spiritual plane.

Jean-Baptiste Willermoz

Highly hypnotizable women known as 'crisiacs' acted as oracles and communicated with the spirit world. They described scenes and personae in the other world, including the dead.[7]

The Lyon mesmerists used a diagnostic technique known as 'doubling', whereby the magnetizer felt the patient’s ailment in his own body. They also placed their patients in trance so that they could see inside their own bodies and make self-diagnoses.[8] In these practices we see the beginnings of what today are sometimes called 'medical intuitives'.

In 1784 these mesmerists conducted three successful experiments at the Lyon Veterinary College in the presence of a large number of witnesses. In one of these demonstrations, two Barberinist initiates were given an ailing horse to diagnose. They announced that the animal was diseased in the lateral and anterior part of the right lung and in the left lung all over, but particularly toward the sixth true rib; and that there were obstructions in the liver and spleen, especially the latter. These diagnoses were proved correct at autopsy.[9]

Magnetizing a horse at Lyon.

The mesmerists of Lyon did not believe in a magnetic fluid like the fluidists. They believed that the cures were the result of will, faith, and an act of God upon the soul.[10] They attributed healing to a divine influx that temporarily returned the individual to man’s original divine condition before the Fall. This view was an expression of their central esoteric philosophy - a spiritual philosophy of 'Reintegration' that went back to Martines de Pasqually.

These Barberinists also emphasized the importance of the magnetizer's will, preparation, and state of mind—an idea that was also important to Paracelsus.

Mesmer was disappointed when he visited the Mesmeric society in Lyon. Although he was influenced by esotericism and gave his mesmeric societies a Masonic character, Mesmer wanted his work to be approved by the scientific community, so he rejected the interpretations of Saint-Martin, Willermoz, and Barberin. Mesmer’s doctrine of animal magnetism was materialistic and asserted the existence of a magnetic fluid.[11]

Nineteenth Century Spiritualist Magnetism

To a large extent the French Revolution from 1789-1799 interrupted the first generation of esoteric magnetists. However, decades later, from the 1840s onwards, there was a so-called “occult revival”, and here we see a revival of Spiritualist magnetism.

The Spiritualist magnetizers induced trance states for the purpose of spirit communication. Their subjects, acting as mediums, could console the grieving by allowing them to communicate with the dead. They could also question historical figures learned in relevant subjects, and find lost or stolen objects.

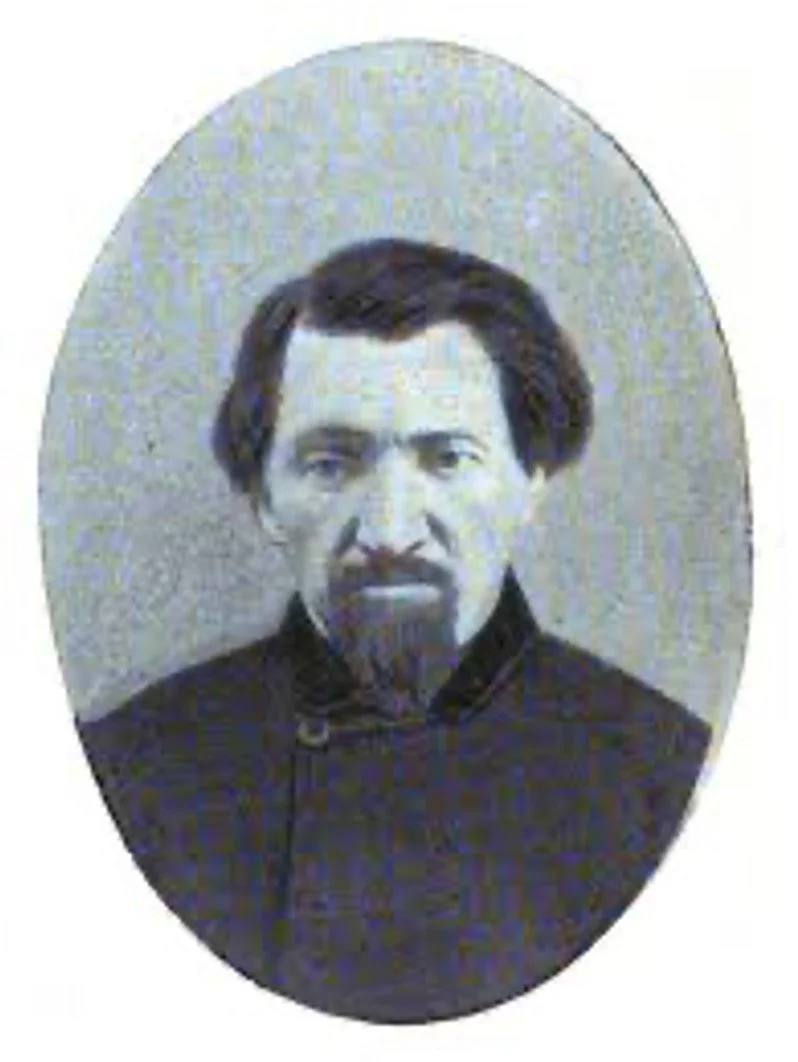

Louis-Alphonse Cahagnet

The most prolific Spiritualist Magnetizer was Louis-Alphonse Cahagnet (1809-1885). Cahagnet was an adept of magic of every kind. His stated aim was to promote the ideas:

that all religions reflect the same divine reality;

that the soul is immortal and that its individuality survives after death; and

that spirits in the afterlife can be contacted.

Cahagnet’s method involved mesmeric passes over the subject, who would then fall into a particular state he called exstasis. In contrast to a trance, which has the appearance of sleep, the subject in exstasis experiences scenes of beauty and happiness, and even religious visions. Once the subject was in this state, Cahagnet would ask him or her questions.

Louis-Alphonse Cahagnet

In Cahagnet’s time, exstasis was usually seen in females of an excitable temperament, especially during religious devotion. Such a person is called an “estatica”. Cahagnet was a follower of Emmanuel Swedenborg's works, and in many of his séances the estatica Adele contacted the spirit of Swedenborg so that Cahagnet could ask about the nature of the afterlife and the abilities of spirits; how to make talismans and magic mirrors, how to induce trance, etc. About Cahagnet’s subjects, it was said:

“Some of them affirm that every man has an attendant good spirit, perhaps also an evil one of inferior power. Some can summon, either of themselves or with the aid of their attendance spirit, the spirit or vision of any dead relation or friend, and even of persons also dead, whom neither they nor the mesmerist have ever seen, whom perhaps no one present has seen; and the minute descriptions given in all these cases, of the person seen or summoned, is afterwards found to be correct.”[12]

One of the most interesting statements frequently made by Cahagnet’s highly sensitive subjects was that they could see luminous appearances emanating from objects and persons, and also that they themselves had a luminous appearance, often described as a halo or glory around the head. His subjects were so sensitive that they could see these emanations in the waking state, even in daylight.

As one might imagine, his work attracted attention, and from the late 1840s he was an object of frightened curiosity, first in England and then his native France. Denunciations and a ban by the Inquisition served only to heighten his reputation.[13]

Cahagnet made his observations with great care. In 1848 he published Magnetism: Mysteries of the future life unveiled in 3 volumes. This was a summary of his experiments with eight somnambulists and their spirit communications with 36 entities that gave detailed descriptions of the celestial spheres and the afterlife. Cahagnet was also editor of The Spiritualist Magnetizer (1849-1851), the short-lived journal of the Society of Spiritualist Magnetizers of Paris.

The Spiritualist Magnetizer, edited by Cahagnet.

Revival of Magnetism

A second wave of important healers emerged in France in the second half of the 19th century.

Jean-Martin Charcot

Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) was a French medical doctor and the founder of modern neurology. He was not a magnetist, but his work was important in the development of hypnotism and psychology. He is included here to place the 19th century revival of magnetism in context.

Charcot worked and taught at the famous Salpêtrière Hospital beginning in 1862. He became interested in hypnosis in the 1870s and 1880s, and his institutional authority at Salpêtrière gave his ideas enormous prestige.

Charcot rejected the ideas of magnetism and spiritism. He also opposed the view of the Nancy school (Liébeault and Bernheim) that hypnosis was produced by suggestion. Charcot believed that hypnosis was a neurological phenomenon associated with hysteria, and that only hysterical patients could be hypnotized.

Jean-Martin Charcot.

In his lecture demonstrations, Charcot produced various symptoms (for example, blindness, deafness, the inability to speak, and paralysis) in his hypnotic subjects, inviting his medical students to verify the authenticity of the symptoms. When he brought his subjects out of the hypnotic state, their symptoms disappeared. Mesmer had demonstrated that the unconscious could heal illness; Charcot’s lectures showed that the unconscious could also produce symptoms of disease. This was a pivotal moment in the scientific study of the unconscious. Sigmund Freud studied with Charcot in 1885 in Paris and was deeply impressed by Charcot’s idea that the unconscious could produce symptoms. This experience steered Freud toward the study of the unconscious – first with hypnosis and later with dreams and psychoanalysis.

Ultimately, Charcot’s theory that hypnotism had a pathological basis was eclipsed by the Nancy School’s theory of suggestion, which offered a psychological explanation of hypnosis. Nevertheless, Charcot’s view that hypnosis is a neurological phenomenon aligns with certain physiological effects of hypnotism, such as lethargy, catalepsy, and somnambulism.

Because Charcot viewed hypnosis as a neurological phenomenon, he used sudden stimuli to induce hypnosis, for example: abrupt verbal commands, loud sounds (e.g., a gong or tuning fork), touch, and bright light. These methods prefigured later approaches to nonverbal induction, such as instantaneous (i.e. “shock”) inductions, and fascination methods that involve the eyes, such as James Braid’s eye-fixation method.

Jules-Bernard Luys

Another highly respected French neurologist, and an associate of Charcot, was Jules-Bernard Luys (1828-1897). Luys made substantial contributions to the knowledge of human brain anatomy. He was elected to the prestigious Académie de Médecine in 1877 and named Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur by the French Government.

Luys was assigned to Salpêtrière Hospital in 1862, the same year Charcot arrived, and both began teaching there in 1866. Luys took up hypnosis around 1883, and in 1886 he left Salpêtrière to become chief physician at La Charité Hospital in Paris. Here he devoted most of his time to the study of hysteria and hypnotism.

In his time Luys was called “the greatest hypnotist in the world”. A contemporary account noted:

"With subjects who have often been hypnotized, the simple word of command, without passes or gestures of any kind, suffices. With these he has but to say, “Go to sleep,” and they fall at once into a hypnotic state. Doctor Luys is, however, the sole possessor of hypnotism I have seen who has this power...”[14]

Jules-Bernard Luys.

In contrast to Charcot’s use of abrupt shocks, such as from loud bells and gongs, Luys induced trance by more gentle means, especially by having his subject fix their eyes on a revolving mirror.

In 19th century France, birdcatchers used a lark mirror—a piece of wood studded all over with small squares of silvered glass, mounted on a stick in such a way that it can rotate. The glittering glass fascinates the birds, and they soon fly down and are trapped in nets. Dr. Luys thought the same method could be used for hypnotizing humans, so he had a similar machine made that operated automatically. One great advantage of Luys' miroir roratif was that it could be used to hypnotize a number of subjects at one time. A contemporary description of the method reported:

“The eyes are first attracted by the rays of light which flash from the wings of the mirror, then little by little, and at the end of a period which varies according to the temperament of the patient, a kind of fascination is produced, the lids get tired and imperceptibly close, the head falls back, and the patient sleeps a sleep which seems natural, but which is really one of the first phases of the hypnotic sleep.”[15]

An advertisement for the motorized mirror claimed: "It is to the hypnotist what the knife is to the surgeon—it is indispensable... Physicians, dentists, professional hypnotists and all students of occultism recommend it."

It is largely due to Luys’ innovation that mechanical aids, such as the spinning hypnotic spiral or a swinging pocket watch or pendulum, are used for fascination in hypnotism.

Gérard Encausse - Papus

Luys was assisted in his work by the Spanish-born physician Gérard Encausse (1865-1916), widely known under the pseudonym ‘Papus’. Around 1887, Papus began working under Luys’ supervision at La Charité Hospital. In 1888, at Luys’ behest, Papus became editor-in-chief of the Revue d’hypnologie, and in 1890, when Luys’ health began to fail, Papus took over as head of the laboratoire d’hypnologie at the hospital.

Several years earlier, in 1882, Papus had been a disciple of the dying Henri Delaage, who was said to have been among the last men with a direct connection to the Martinist secret societies of the late 18th century. As Papus became intensely involved in the medical study of hypnosis, he was simultaneously gaining a reputation in the esoteric world:

1888, Founded the Kabbalistic Order of the Rose-Croix with Stanislas de Guaita, Joséphin Péladan, and Oswald Wirth.

1891, Founded l'Ordre Martiniste, claiming to possess the original papers of Martinez de Pasqually.

1893, Consecrated as a Bishop of l'Église Gnostique de France, known as the “Church of the Initiates”.

1895, Became a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.

Papus’ career illustrates the continued synthesis of hypnotic practice and esoteric philosophy well into the late 19th century, demonstrating that mesmerism never fully abandoned its mystical roots, even in a medical context. He wrote that his studies had shown him materialism was a radically incomplete way of looking at the world, and that transcendental forces played crucial roles in all aspects of life.[16]

‘Papus’ in his oratory.

Luys’ Experiments

Luys conducted sensational experiments in hypnosis, prompting gossip and scandal. All of Paris gathered at his public performances, which newspapers wrote about in their entertainment sections.[17]

“Direct Cures” by Transfer

Luys was able to transfer physical, mental, and emotional states and symptoms from one person to another. The method involved a trained hypnotized subject sitting opposite a patient, clasping hands, or in some cases laying hands on the patient’s head. Luys would then pass a magnetized iron bar over the arms and body of the patient in order to draw out the diseased ‘effluvia’ and pull them into the body of the hypnotized subject. With each pass, the subject would experience an involuntary convulsion. The transfer usually lasted about three minutes. During this process, the hypnotized subject also could answer the doctor’s questions about the patient’s condition and progress.

Through this transfer the hypnotized subject acquired the symptom of the patient (and generally his personality as well). In the end, the patient would feel much better, and the hypnotized subject would be cleared of the acquired symptoms by hypnotic suggestions and considerably benefited.

Luys conducting his experiments.

Transfer with iron crowns: Magnetothetapy / Metallotherapy

In 1891 Luys and Encausse announced before the Society of Biology that an iron crown placed on the head of a patient was capable of absorbing and preserving pathological biomagnetic effluvia. Disorders could then be transferred to a second patient by placing the same crown on his or her head.[18] Dr. Luys used a piece of iron curved into the shape of a horseshoe big enough to fit over a human head and fitted with straps as low as the temples and no lower. He placed this on his own head and came forward, saying, “This is a wonderful tank. It is a tank for the storage of temperament.”[19] This discovery suggested: if pathological nervous states could be artificially absorbed, stored, and transferred, then perhaps healthy ones could as well. [20]

Seeing the magnetic effluvia

One interesting phenomenon demonstrated by Dr. Luys was that when a magnet was presented to a hypnotized subject, the effect produced varied depending on whether the north or south pole of the magnet was used. The north pole produced a state of intense delight, expressed by gestures and outcries of pleasure. The subjects in these cases declared that they saw a beautiful blue light emanating from the end of the magnet. When the bar was reversed, the subject would feel horror and disgust at the sight of a fearful red light playing around the end of the magnet.[21]

Early in the 1890s, they also began to report that certain highly sensitive subjects were able to see the magnetic effluvia radiating from the bodies of living beings (notably the doctors themselves).[22] Luys discovered that the hypnotized subject can detect in the human face emanations like those seen at the ends of the magnet. If the person was in good health, the right side was distinguished by blue flames issuing from the right nostril, the right ear, and the right eye; while the left side was similarly marked by red flames. Thus, in the parlance of hypnotism, people were said to have their red and their blue sides. However, in cases of persons suffering from nervous disorders, diseases, or accidents, the colors varied.[23] In Luys’s view, opposite emotions resided in the left and right halves of the body. They called this the “Doubling of the Personality”.[24]

Medicine at a distance

In his later experiments, Jules-Bernard Luys placed sealed glass vials containing drugs such as morphine, strychnine, alcohol, or hashish near hypnotized patients and recorded dramatic effects. Morphine produced pupil contraction, drowsiness, and a narcotic-like state; strychnine caused muscular tension or convulsions; and alcohol led to excitement and laughter. In 1890, Luys wrote The Emotions in the Hypnotic State, and The Action-at-a-Distance of Medical and Toxic Substances.

Collectively, Luys’ experiments represented a remarkable moment in 19th-century mind-body research, a period when science, medicine, and esoteric exploration were deeply intertwined. In his own time, Dr. Luys’ gentle method with the rotating mirror and experiments with magnetic effluvia revealed phenomena of fascination, magnetism, and hypnotism that were previously unknown.

Luys’ subject reacts to medicine in a sealed vial.

Conclusion

From the early experiments of Mesmer to the elaborate esoteric systems of the nineteenth century, magnetism and the Western esoteric tradition continually shaped and reinforced one another. In the late eighteenth century, Mesmer's theory of a subtle fluid resonated strongly with the spiritual philosophies of Saint-Martin, Willermoz, Barberin, and the mystics of Lyon. Their practices, ranging from somnambulic diagnosis and medical intuition to spirit communication—demonstrated that magnetism could be a bridge between bodily healing and metaphysical insight. This first wave of interaction was interrupted by the Revolution, but its ideas remained embedded in the esoteric orders that survived it.

Decades later, after the French Revolution and the first generation of magnetists, these same themes re-emerged in new scientific and esoteric contexts. The work of Charcot and Luys at the Salpêtrière brought hypnosis into medical respectability, while revealing phenomena that echoed the earlier fluidist and spiritualist interpretations. Meanwhile, figures like Cahagnet and Papus carried forward the tradition of magnetic practice within explicitly esoteric frameworks. Papus’s career in both hypnotic medicine and the Kabbalistic and Martinist orders crystallized this second period of synthesis, prompting the French commentator Jules Bois in 1895 to describe the esoteric societies of his day as “half temple, half magnetizer’s office.” This demonstrates the degree to which mesmerism continued to be part of the practical work of the Western esoteric tradition.

Across these two eras, a consistent pattern emerges. Magnetism gave esoteric thinkers a practical method for exploring invisible forces, while esoteric philosophy offered magnetizers a metaphysical language to interpret their results. The dialogue between the two shaped the development of hypnotism, influenced modern conceptions of the unconscious, and preserved within the Western tradition a sense that healing, perception, and consciousness itself are linked to forces that operate beyond the limits of the senses.

Sources

[1] Mesmer, F. A. (1840). Mesmerism: A translation of the memoirs of the celebrated Dr. Franz Anton Mesmer (p. 62). Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy.

[2] Mesmer, F. A. (1840). Mesmerism: A translation of the memoirs of the celebrated Dr. Franz Anton Mesmer (p. 82). Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy.

[3] Mesmer, F. A. (1840). Mesmerism: A translation of the memoirs of the celebrated Dr. Franz Anton Mesmer (p. 71). Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy.

[4] (1938). Great theosophists: Anton Mesmer. Theosophy, 25(10).

[5] Britten, E. H. (1884). Nineteenth century miracles; or, spirits and their work in every country of the earth: A complete historical compendium of the great movement known as "modern spiritualism" (p. 119). Lovell & Co.

[6] Darnton, R. (1968). Mesmerism and the end of the Enlightenment in France (p. 87). Harvard University Press.

[7] Lachman, G. (2008). Politics and the occult: The left, the right, and the radically unseen (p. 87). Quest Books.

[8] Turner, C. (2006). Mesmeromania, or, the tale of the tub: The therapeutic powers of animal magnetism. MagazineKiosk, 21, Spring.

[9] Goodrick‑Clarke, N. (2008). The Western Esoteric Traditions: A Historical Introduction (p. 120). Oxford University Press.

[10] Goodrick‑Clarke, N. (2008). The Western Esoteric Traditions: A Historical Introduction (p. 180). Oxford University Press.

[11] Podmore, F. (1909). Mesmerism and Christian science: A short history of mental healing. G. W. Jacobs.

[12] Gregory, W. (1877). Animal magnetism: Or, Mesmerism and its phenomena (p. 85). William H. Harrison.

[13] Fox, R. (2012). The savant and the state: Science and cultural politics in nineteenth-century France (p. 203). Johns Hopkins University Press.

[14] McClure's Magazine. Volume 1. 1893. Pages 549-550.

[15] McClure's Magazine. Volume 1. 1893. Pages 549-550.

[16] Monroe, J. W. (2018). Laboratories of faith: Mesmerism, spiritism, and occultism in modern France (p. 238). Cornell University Press.

[17] Chéroux, C. (1997). Attempts at photographing life forces: Freudian slides – 1. In Im Reich der Phantome: Fotografie des Unsichtbaren (pp. 11–22). Cantz.

[18] Bynum, W. F., Porter, R., & Shepherd, M. (Eds.). (2003). The anatomy of madness: Essays in the history of psychiatry(Vol. 3, p. 235). Routledge.

[19] Current Opinion. (1895). With the World's Greatest Hypnotist (Vol. 18, p. 444). In Scientific Problems, Progress and Prophesy. Current Literature Publishing Company.

[20] Bynum, W. F., Porter, R., & Shepherd, M. (Eds.). (2003). The anatomy of madness: Essays in the history of psychiatry(Vol. 3, p. 235). Routledge.

[21] McClure’s Magazine. (1893). McClure’s Magazine (Vol. 1, p. 552). S. S. McClure, Limited.

[22] Bynum, W. F., Porter, R., & Shepherd, M. (Eds.). (2003). The anatomy of madness: Essays in the history of psychiatry(Vol. 3, p. 235). Routledge.

[23] McClure’s Magazine. (1893). McClure’s Magazine (Vol. 1, p. 552). S. S. McClure, Limited.

[24] Luys, J. B. (1887). Les émotions chez les sujets en état d’hypnotisme: Études de psychologie expérimentale faites à l’aide de substances médicamenteuses ou toxiques impressionnant à distance les réseaux nerveux périphériques (p. 1178). Paris: Baillière.